Introduction

There are many ways to read a map. One of my favorites is to discover something in the map that was not necessarily drawn as a principal feature or intended as the subject of the map itself but which, in fact, once identified, reveals another major theme of the map. This element might be the map publication date, or an image, or an unlabeled feature or a fragment of text. This revealed theme might arise from the map itself as if the map were a kind of hologram that, when tipped to its side, shows a competing image. This essay is about how in reading a map, we might look for such clues, and in particular, how we might do so where the subject matter of a map is a city or town or urbanization itself.

This essay is an exercise about critical reading. In keeping with the theme of this edition of the Calafia Journal, for this four-part essay series, I have chosen different kinds of town or city maps (American) published or authored in the 19th and 20th c. that I have studied in the past few years. My research into each of these maps began with a focus on each work's art, symbolism, geography, author, and explicit themes. The discovery in each instance was that hiding in “plain sight” was at least one feature of each map that also revealed an unanticipated story. Looking at an antique or contemporary map for camouflaged themes intrigues me for a variety of reasons. One reason is that it provides motivation to read a map deeply. Another reason is that looking for complexity in the art of each map sharpens one's eye for discerning persisting themes of American thought and culture. This kind of critical thinking eschews formulas or ideology and permits the creative pleasure of wondering why. An antique or historic map thus revealed becomes as contemporary as the ideas it embodies.

We will examine a mid-19th c. Maine town wall map, an early 19th c. manuscript surveyor's plan of land in Georgia, a WWII era American Red Cross map of Paris for U.S. service-men and women, a 1940 Seattle urban transit route map, an early 20th c. Montana and environs mining town map and a 1926 Boston Planning Board zoning map. I will suggest topics revealed by a close reading of each of these maps. In some cases, these are urban planning or land use issues. In one example, the topic is the integrity of surveying itself and the role of land recording systems. One example also gives rise to consideration of a map's format as an independent element of meaning. Hiding in plain sight are additional topics that were and continue to be major American themes. That is not to say it was the intent of each map's author to showcase such themes—although it might have been.

The six maps1 in this four-part essay series are:

- Map of the Town of Ellsworth Hancock Co. Maine from Actual Survey by D.S. Osborn, E.M. Woodford, publ., Philadelphia, 1855

- Georgia. Daniel Sturges, Surveyor General of Georgia (manuscript) Certified Survey Plan dated April 21, 1808, Milledgeville, Georgia

- American Red Cross Map of Paris. Blondel La Rougery, Paris 1945

- Seattle Transit System Operation as of May 12 1940. [Seattle, Washington]

- Map of the Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana Compiled and Published by Harper, Macdonald & Co. Butte, Silver Bow County Montana 1907

- Map of the City of Boston Massachusetts Published by The City Planning Board November, 1926. [Boston, Massachusetts]

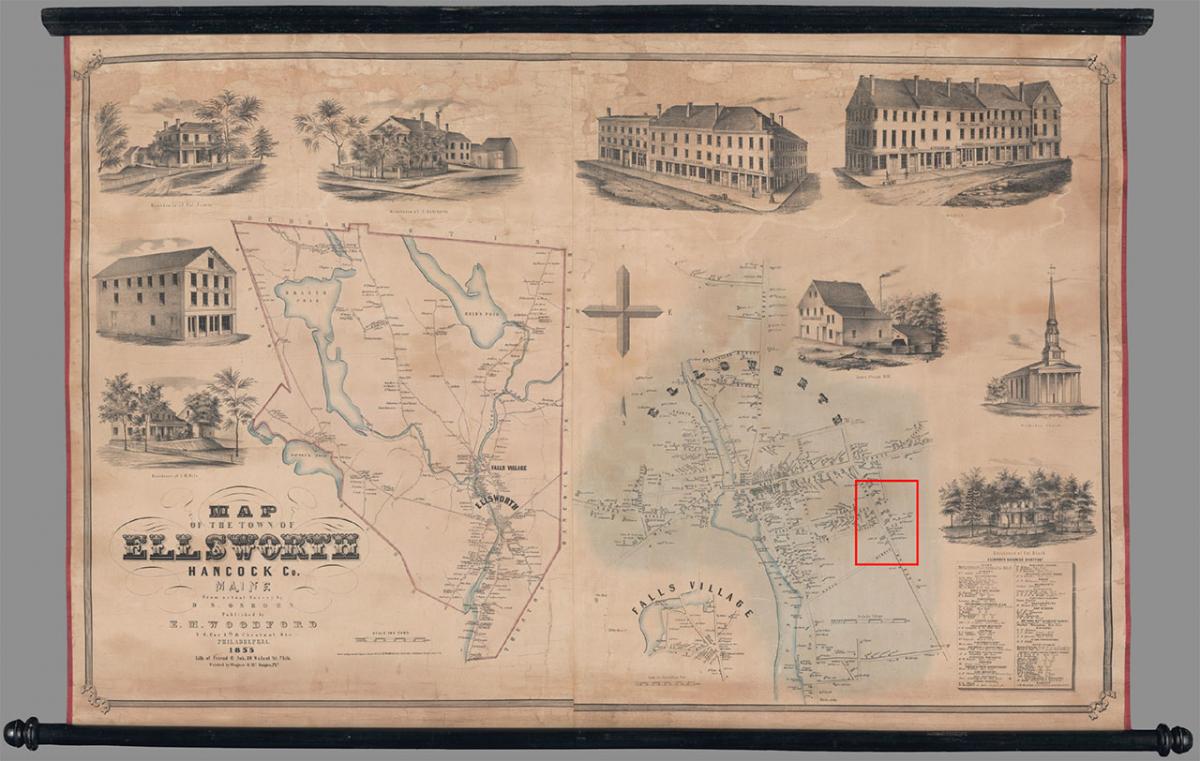

Figure 1. Osborn, D.S. 1855. “Map of the town of Ellsworth, Hancock Co., Maine, From actual Survey by D.S. Osborn” Image courtesy of Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine. https://oshermaps.org/map/54257.0001.

Figure 1. Osborn, D.S. 1855. “Map of the town of Ellsworth, Hancock Co., Maine, From actual Survey by D.S. Osborn” Image courtesy of Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine. https://oshermaps.org/map/54257.0001.

(1) Map of the Town of Ellsworth Hancock Co. Maine from Actual Survey by D.S. Osborn (1855)

E.M. Woodford's rare, large scale illustrated 1855 wall map of Ellsworth, the county seat of Hancock County, Maine, captures Ellsworth as a thriving town near the height of its industrial strength in shipbuilding and manufacturing. Osborn's survey and the accompanying pictorial vignettes together present the civic and geographic character of the town fifty-five years after its founding. Hancock County, a rural but resource-rich region, poured its resources into Ellsworth as the county seat both for local consumption and for export. Remarkably, in 1855 there are yet no railroads in Hancock County, and much of this commerce was conducted under sail or by wagon.2

The Map of Ellsworth, 1855 (Fig.1) is a work of geography, history and art, the map's urban features illustrated with finely drawn architectural vignettes, local scenery and decorative lettering in E.M. Woodford's aesthetic style. These pictorial vignettes dominate the top half of the map, showing scenes of daily life, one church, main street, the homes of prominent citizens. A business directory visually anchors one corner of the map. The lithographer uses the texture of his stone for subtle shading in the landscape scenes. The large scale vignettes show certain Ellsworth buildings that exist today. The town map and inset village map locate and identify homes, businesses, churches, schools, factories, and other structures on the map. Most of these are labeled with owners' names. Some are not. Complete and less formal roads are shown in solid or hatch marked lines, another town plan device.

The Ellsworth town plan is also a traditional New England mid-19th century plan of a river town. The Map of Ellsworth, 1855, shows a town that grew up along both banks of the Union River, a major watercourse with an outlet to the seacoast. The town center to the west includes town and county government, law, estates, and a Baptist church. The essential town functions reach beyond town and state boundaries via the Union River. On the east side of the Union River is Main Street, School Street, the location of a school (public) and private schools, a Congregational church, and business establishments. Much is within walking distance. Settlement becomes less dense on the town's eastern periphery and roads less formal. Industry is concentrated in Falls Village, where water power from the waterfall is available. The town plan at its outskirts dissolves to open blocks of land.

The 1855 Ellsworth business directories reveal a myriad of trades, all characteristic of a thriving mid-19th c. American seaport region. The list includes merchants and fishing outfitters, including C.E. Jarvis & Co., Mrs. Parker's Millinery, R.H. Bridgham the physician and surgeon. The Collector of Customs, Inspector of Customs and Postmaster, Town Clerk, and Sheriff are named. Relative to the other Hancock County towns, Ellsworth has both the largest professional population and a list of merchants and skilled tradesmen and women. Ellsworth was the county commercial center and offered the services of a watchmaker, the druggists and apothecaries, master shipbuilders, land surveyors, the Telegraph Operator, the Ellsworth Gas and Light Company, painters and glaziers, insurance agencies, and dry goods and groceries. The 1855 Ellsworth business directory highlights Maine's major industries, lumbering, shipbuilding, and businesses serving a prospering clientele.

There are no population statistics on this map. The absence of population statistics presents a question hiding in plain sight. How can we understand the manpower required to staff the factories at Falls Village, build and crew the ships and support the thriving local economy? Without map population statistics, the cause and effect on Ellsworth in 1855 of a rapidly growing mid-19th c. American population must be inferred. Other research also sheds light on this topic and is hiding in plain sight on the map.

The years 1854-55, when the map was surveyed and published, were the brief period of the Know Nothing movement in Maine. Between these dates, Ellsworth was the setting for a notorious political event called the "Ellsworth Outrage" carried in national newspapers. The local Know-Nothing party found its local voice in the Ellsworth Herald, edited by William Cheney and later titled the Ellsworth American, whom some suggested fomented the controversy to save his failing newspaper. In Ellsworth, the small Know-Nothing party went by the name the "Cast Iron Band" that had an anti-immigrant platform. Other Maine newspapers, within and beyond Ellsworth and the body of Ellsworth residents denounced the Cast Iron Band and rejected its anti-immigrant posture. The Know Nothing Party arose in the context of rapidly rising immigration to Maine which by 1850, had reached approximately 100,000 new immigrants primarily from Ireland, and some French Canadians bringing a large, new population of Catholics to Maine towns.

Figure 2. Detail: Map of the Town of Ellsworth

In this time of rapid social change, Catholic Jesuit priest Father John Bapst moved to Ellsworth to establish a Catholic church, and a Catholic church is shown (Fig. 2) on the Map of Ellsworth, 1855 far from the downtown, located on High Street, between Elm and Deane Streets the sole structure in this large tract on the town outskirts. Even the streets defining this tract are shown with hatch marks. Father Bapst was one of a small number of Catholic priests in Maine, and his story is told in detail by the dissertation noted below upon which these comments are based.3 Father Bapst also oversaw a new Catholic school connected to the church to teach congregants' children who had been expelled from the Ellsworth public school for being unwilling to read from the Protestant King James Bible as it violated their church teachings. The Catholic church school teacher was a lay town resident. Father Bapst joined with one congregant in mounting a legal challenge to the Ellsworth School Board requirement that school attendance was mandatory, that the curriculum required study of the King James Bible, and students who refused to read from this bible would be expelled. Father Bapst did not prevail in Donahue v. Richards, the Maine Supreme Court holding that the School Board was within its proper authority. The 1820 Maine Constitution guaranteed free exercise of religion.4 Here is a mid-19th c. example of American constitutional history and of the frequent gulf between a state constitution's grant of the right of free exercise of religion, and the mechanism of its exercise.

Figure 2. Detail: Map of the Town of Ellsworth

In this time of rapid social change, Catholic Jesuit priest Father John Bapst moved to Ellsworth to establish a Catholic church, and a Catholic church is shown (Fig. 2) on the Map of Ellsworth, 1855 far from the downtown, located on High Street, between Elm and Deane Streets the sole structure in this large tract on the town outskirts. Even the streets defining this tract are shown with hatch marks. Father Bapst was one of a small number of Catholic priests in Maine, and his story is told in detail by the dissertation noted below upon which these comments are based.3 Father Bapst also oversaw a new Catholic school connected to the church to teach congregants' children who had been expelled from the Ellsworth public school for being unwilling to read from the Protestant King James Bible as it violated their church teachings. The Catholic church school teacher was a lay town resident. Father Bapst joined with one congregant in mounting a legal challenge to the Ellsworth School Board requirement that school attendance was mandatory, that the curriculum required study of the King James Bible, and students who refused to read from this bible would be expelled. Father Bapst did not prevail in Donahue v. Richards, the Maine Supreme Court holding that the School Board was within its proper authority. The 1820 Maine Constitution guaranteed free exercise of religion.4 Here is a mid-19th c. example of American constitutional history and of the frequent gulf between a state constitution's grant of the right of free exercise of religion, and the mechanism of its exercise.

Violence against Father Bapst before the court case had once threatened his life and next reached a horrific peak when he was abducted by a group from the Cast Iron Band, taken to the town piers, tarred and feathered, and rode out of town attached to an iron rail. Col. Charles Jarvis, a town leader, and friend of Father Pabst, came to his rescue as he had previously. The Ellsworth wall map shows the Col. Jarvis house and several Jarvis named buildings. After being attacked and brief respite at Col. Jarvis' home, Father Pabst left Ellsworth and moved to Bangor to recover. He then settled in Boston, Massachusetts, and worked with others to establish Boston College located in Newton and Boston, Massachusetts.

The map's publisher would have been aware of this political incident given its national profile, albeit brief and now largely unknown. Is there anything on this map that explicitly reveals the story? Hiding in plain sight is the one church building outside of the town center and at its outskirts where little else has yet been built. The outlying church building is labeled "CATH CH" and has no cemetery. There is no pictorial vignette on the map of the Catholic church. While we know from town history that there was a church school building, its location on the map is not labeled. It might have been nearby on High Street. We can locate on the map the route of father Bapst's abductors, the town piers where he was tarred and feathered, and Col. Jarvis' home.

I did not initially understand that hiding in plain sight on the Ellsworth wall map was a new community of Irish Catholic immigrants to America. Nor did I immediately appreciate that this map's date, 1855 was a political flashpoint in mid-19th century America, a time of unprecedented new immigration to American cities and therefore a clue to a theme in the map. How else were the factories staffed at Falls Village, the ships built to meet the demands of a national economy and the town plan itself expanded. The aesthetic Ellsworth town map is an American paper tapestry and a portrait of Ellsworth in metamorphosis: a town map that is equally pictorial vignettes of one church, fine homes, two large 19th c. professional blocks on its Main Street and a steam mill, and there at its unbuilt outskirts one curious Catholic church.

Conclusion

We have examined the first map in this series of six 19th and 20th c. town and city maps, each of a different type and each accompanied by an essay that discusses questions hiding in plain sight raised by that map. The remaining five city and town map essays will appear in the next three issues of Calafia. These six essays are to be read as one article.

Art and the language of 19th and 20th c. maps have many dimensions of meaning not by chance but because language, letters, colors, materials, and art are that rich and act as prisms of meaning. The impetus for this article is to share my pleasure closely reading American 18th, 19th or 20th c. maps for many kinds of meaning to discover hiding in plain sight the themes, issues and debates that endure.

Carol Spack brings a lifelong love of writing to her activities as collector and dealer in Americana and antique maps. She understands antique maps as art, as history and as ongoing discourse. Her life experience in art, law and land use planning drew her to the theme of this issue of Calafia.

- 1. For full map particulars and, in some cases, an extensive es-say on each of the maps discussed here, please read further at www.spackantiquemaps.com.

- 2. Please consult the Original Antique Maps catalog for a description of Henry Walling's Topographical Map of Han-cock County, Maine 1860.

- 3. See, "Father John Bapst and the Know-Nothing Movement in Maine," Anatole O. Baillargeon, O.M.I., Thesis presented to Faculty of Arts of Ottawa University for the degree of Master of Arts, Bar Harbor, Maine 1950. In the Library of Univ. Ottawa.

- 4. Maine Constitution. 1820 - viewcontent.cgi